by

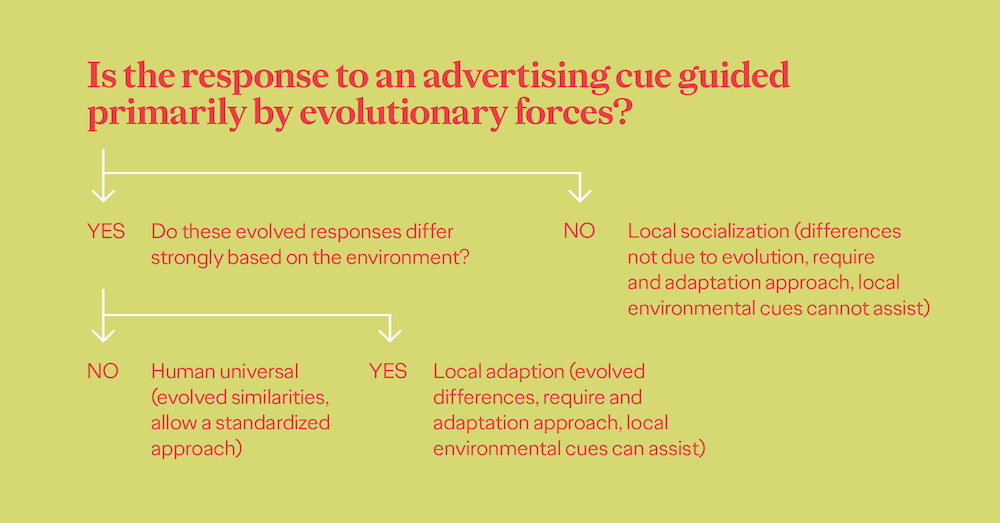

In a recent issue of the Journal of Innovative Marketing, Jordan Buck (Ogilvy Consulting Behavioural Science Practice), Lachezar Ivanov (European University Viadrina) and Rory Sutherland (President, Ogilvy UK published a paper on what advertising can learn from evolutionary psychology. This article provides a top-line overview of the thinking it contains. Please do check out the full version of the paper! There is an important debate within advertising, centered around ‘standardization’ versus ‘adaptation’. ‘Standardization approaches’ suggest that the same advertisements can be used globally, as people around the world are all human and thus all respond in similar way to similar cues. The ‘adaptation approach’, on the other hand, suggests that because different environments affect how people respond to different cues, individual advertisements should be adapted for the local environment. Despite a plethora of studies on the topic, little consensus has been achieved and the debate continues. In his review paper spanning 40 years of research on the debate, Agrawal (1995) pointed out that practitioners are more likely to favor the standardization approach, whereas academics tend to favor the adaptation approach. Agrawal explains this contradiction as a result of the inability of academics to provide practitioners with practical frameworks for decision-making in the real world. Our paper sets out to fill this gap, using evolutionary psychology to provide practitioners with a framework that they can actually use to determine when — and to what extent — a standardization approach should be used in planning, creating and designing adverts. In the paper, we suggest that any trait or behavior can be fit into one of three categories: human universals (evolved similarities), local adaptations (evolved differences), or local socializations (differences not due to evolution). The answers to two questions allow the classification of advertising cues into one of these three categories, as can be seen in the chart below:

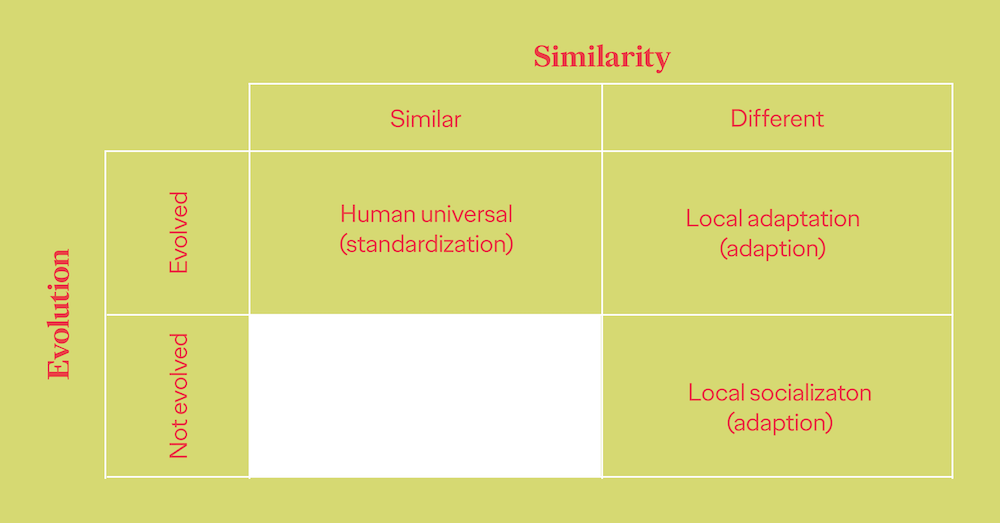

These three categories can also be explained using our “evolution-similarity matrix”, below. The matrix shows that there are two factors that marketers should consider when deciding whether or not to use a standardization approach: whether the response is evolved or not, and whether the response is similar or different across environments.

We then provide detailed explanations of each of these category types, with examples from advertising and marketing. Below is a short summary of each.

1) Human universals (evolved similarities) Everything in this category has been shaped by evolution, meaning people all across the world have evolved to respond in a similar way to certain cues. For these kinds of responses to have spread across the whole human population, they must therefore have provided a strong adaptive advantage in our evolutionary past. For example, men in cultures across the world show a preference for the hourglass figure in women. This preference would have been adaptive in our evolutionary past because the hourglass figure has been demonstrated to be a reliable cue of fertility and health (Singh, 2002). As a result, this preference is found in widely different racial populations, cultures and environments all across the world (Singh, Dixson, Jessop, Morgan, & Dixson, 2010). Using an hourglass figure within an advert would therefore be expected to elicit the same reaction across multiple different cultures, suggesting that a standardisation approach works well for this cue. Indeed, there are various pieces of evidence from advertising research which support this claim — most interestingly, even hourglass-shaped anthropomorphized packages of consumer goods have been shown to elicit aesthetic appeal in consumers (De Bondt, Van Kerckhove, & Geuens, 2018).

2) Local adaptations (evolved differences) Everything in this category has been shaped by evolution so that humans in different environments respond differently to the same cues. These responses would therefore have evolved as adaptations to some feature of the local environment, rather than evolving in exactly the same way all across the world. For example, humans around the world all have evolved a preference for ‘personal space’, i.e. some buffer zone of space around them that they feel uncomfortable if someone else intrudes. However, the average size of these personal space buffer zones differs in a predictable way depending on the environment. Specifically, the average temperature of the environment. In warmer countries, people prefer to maintain and tolerate closer distances toward strangers, whereas in colder counties, people prefer to maintain a greater distance toward strangers (Ijzerman & Semin, 2010; Sorokowska et al., 2017). Even within the United States, people in warm latitudes tend to prefer closer contact with more touch than their counterparts in colder climates (Andersen, 1988). When designing effective advertisements, it therefore makes sense to take into account the local norms for personal space when considering how close together characters should stand and other related features.

3) Local socializations (differences not due to evolution) Everything in this category contains differences that have not been shaped by evolution. Instead, they have been shaped purely by local cultures and norms. Unlike local adaptations, there is nothing inherent in the environment that can enable us to predict these differences. For example, there is strong evidence that humor appreciation varies across cultures, with different cultures around the world varying significantly in what they find funny (Alden, Hoyer, & Lee, 1993; Toncar, 2001; Unger, 1995). In contrast to the case of local adaptations, there are no cues in the environment that can be used to reliably predict what people in different environments will find funny, as this is not a trait that has evolved in response to the environment. Academics have therefore concluded that humor is a rather bad global traveler (Crawford & Gregory, 2015; Gregory, Crawford, Lu, & Ngo, 2019). As a result, practitioners should use an adaptation approach whereby humor is tailored to the specific local market.

Closing thoughts We hope that this paper provides a useful framework for making cross-cultural advertising decisions in the real world. By asking the right questions, advertisers and practitioners can identify which advertising cues are malleable and should be changed and which are based on innate human preferences and are relatively stable. With that knowledge in hand, they can decide when, and to what extent, to use a standardization approach versus an adaptation approach.